Dimension 3

It All Revolves Around This

Home at last, three dimensions. We can get from two to three dimensions in the same way as before, tack on another dimension, gesture at the pythagorean theorem, and call it good. This gives us a position in three 3 dimensions that we can add, subtract, and scale as desired.

We would like to extend our ability to rotate into three dimensions and write down a corresponding algebra. We have previously noted that each component of behavior needs its own element. Lets look at the components of a 3d rotation.

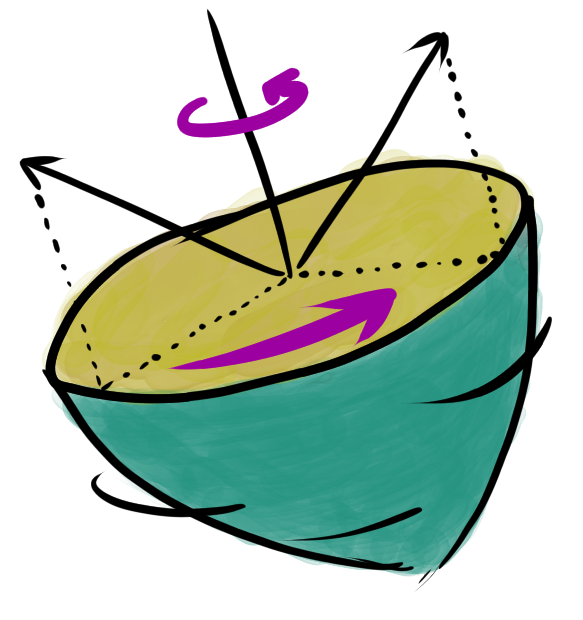

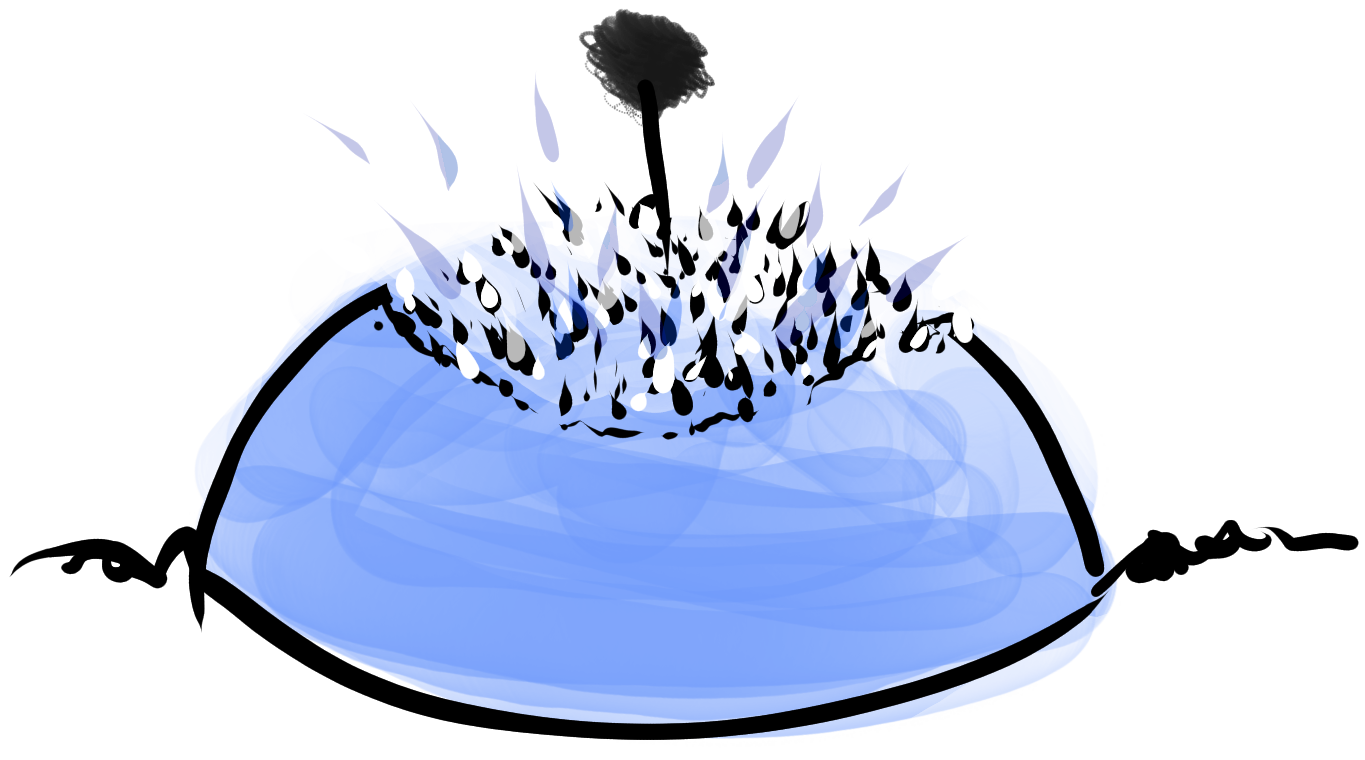

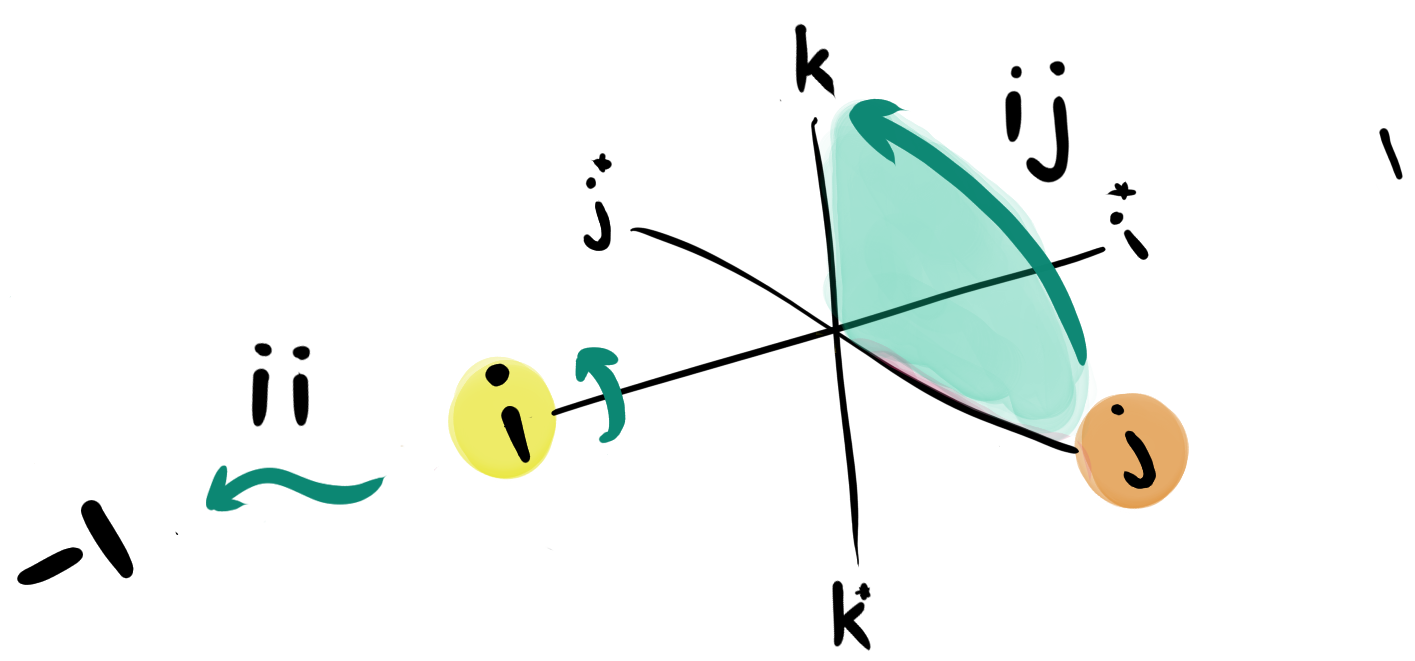

The basics are similar to 2 dimensions in that a rotation clearly involves an exchange from one direction to another in a cycle. The main difference is that in 3 dimensions there is an axis of rotation that goes along for the ride, without any exchanging. We can picture a top spinning on its axis:

Therefore, in addition to knowing how much we want to rotate, we also need to know the axis of rotation.

First, we'll need to figure out how to rotate. Then, just like with 2 dimensions, we can use the pythagorean theorem to transition between staying and rotating. In the 2D case, the rotation behavior was relatively straightforward, involving a swap and a flip to get the four directions going in a cycle. In the 3D case, there is an additional "rotating in place" behavior along the axis, alongside the cycling components. That is to say, when doing a quarter rotation around the first axis we expect our translated point to be:

Where the first component is on the axis of rotation, and and are in the plane of rotation.

A Bubble Bursts

The Singularity is Here

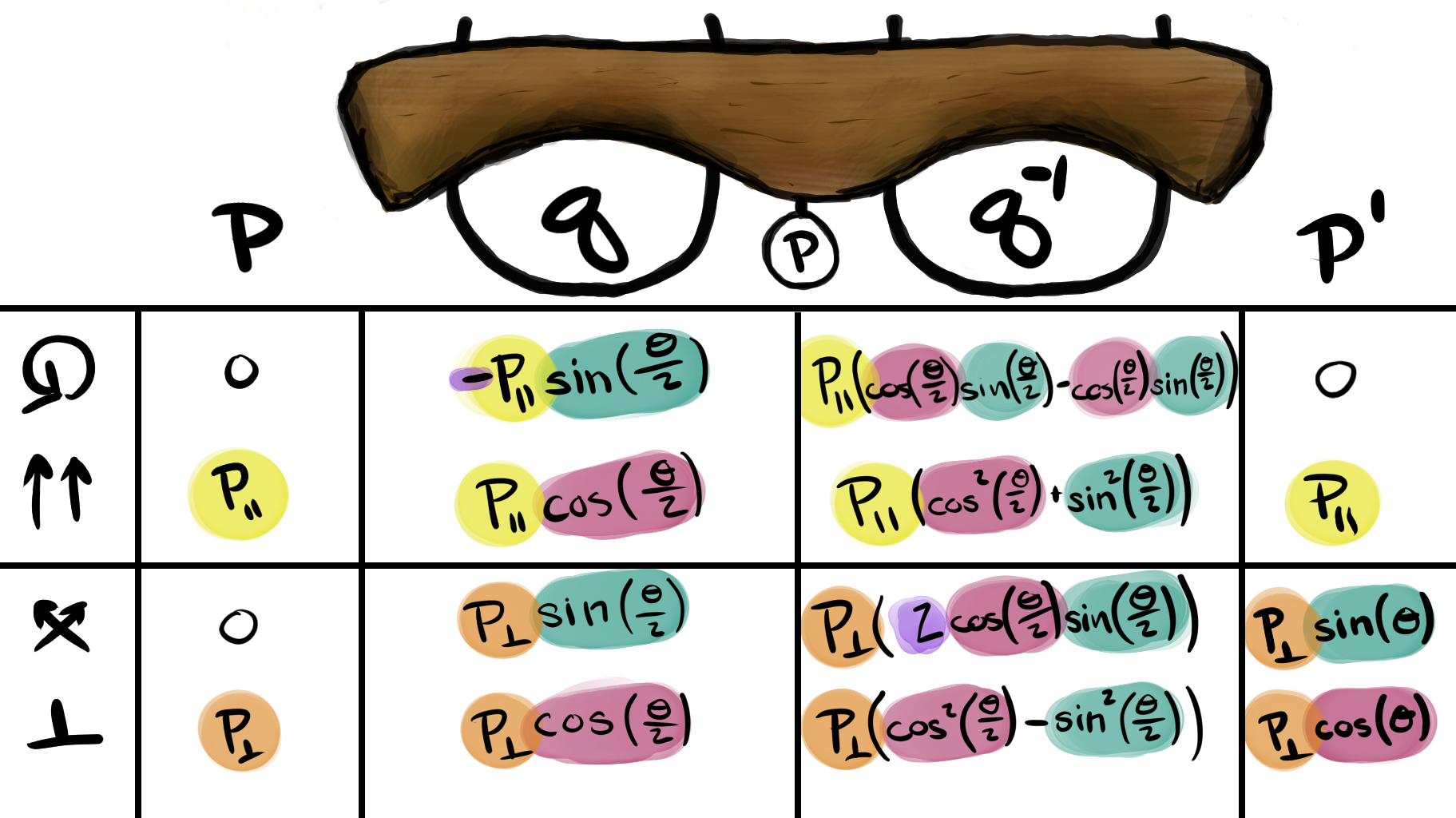

Suppose we keep the exact same setup as in two dimensions and add an additional complex variable. Each can rotate in its plane, but stays still while the other is rotating:

This does indeed allow us to rotate in these two planes, but there are some strange things afoot. The first is that . The order of actions can no longer be switched, they no longer commute ("commute" means "change together"). This is reflecting the fact that we have to be clear which axis is doing the rotating and which is being rotated. Doing rotations in reverse order does not usually result in the same translation. This is contrary to two dimensions in which we could exchange the order freely, and only the total amount of rotation mattered. Given this issue of axes rotating each other, losing commutativity appears to be an unavoidable complication.

Moving on to the second issue and, unfortunately, it is catastrophic. We can see it by substituting into itself:

Its all collapsed! What happened!? The issue is we are trying to get these elements to perform double duty. The first statements, like , tell them to act as rotations, while the second statements, , tell them to act as the identity. But when we combine these behaviors into a single statement, the algebra collapses back into the singularity, the only place where both of these behaviors can be part of the same action! Similarly, if and dont affect each other, how could we rotate between them? We cannot expect to step in and cause a rotation or else we will overload it's behavior as well, ending in another catastrophe.

The Third Wheel

Two is Company, Three's a Crowd

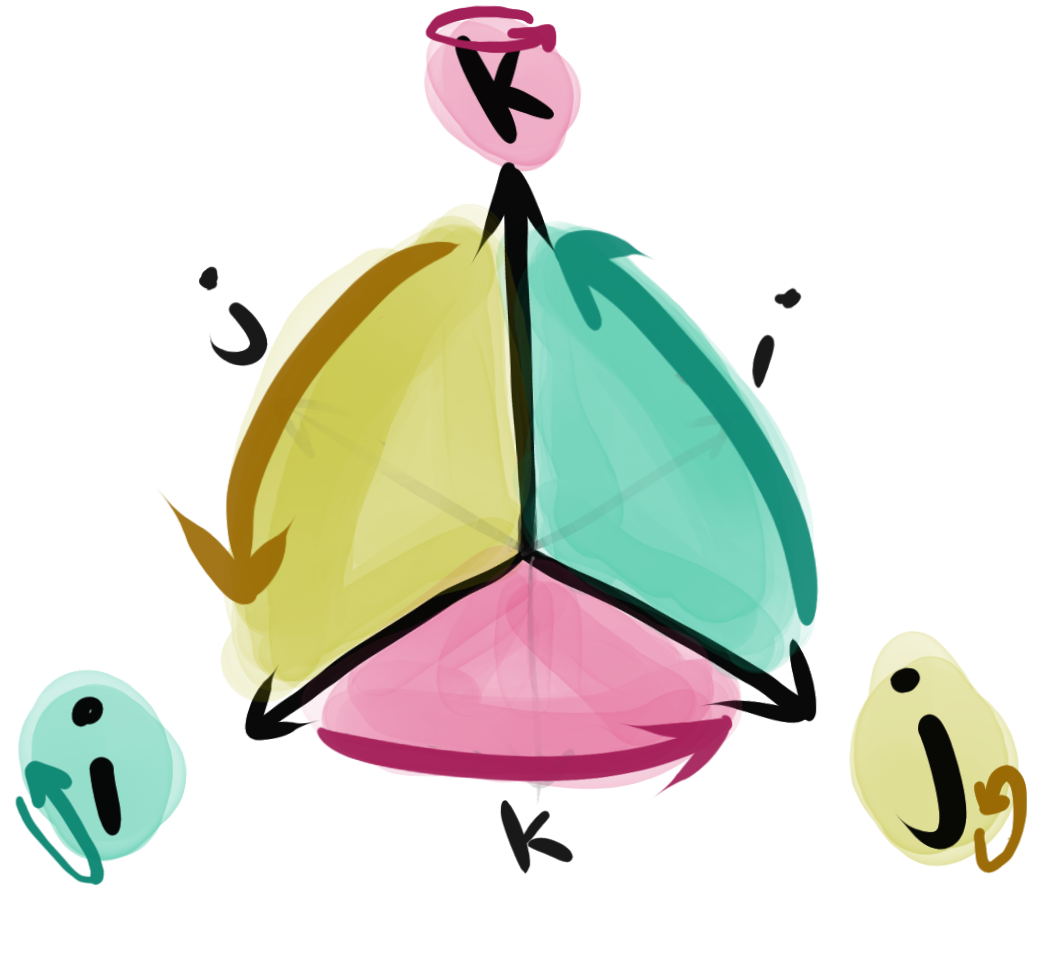

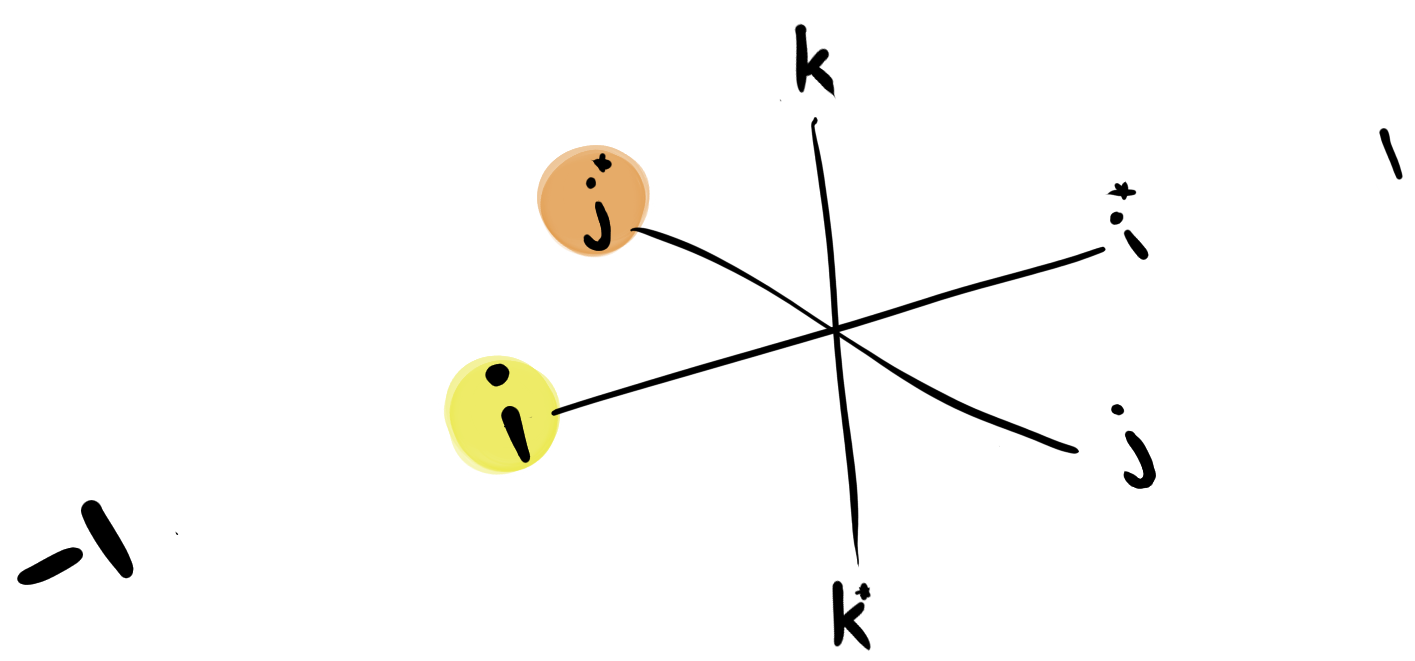

In 2 dimensions, we had only one possible plane of rotation and were able to use a single algebraic variable to represent turning in that plane. Conveniently, this allowed us to think of points both as positions and actions and to freely switch between perspectives. Now that we have three possible planes of rotation, however, not only do we need a variable for each one, but we still need extra room for information about how much to stay vs rotate at all. Therefore, looking ahead, we expect terms in our algebra to have the general form:

Each complex variable represents a quarter rotation in one of the planes / around one of the axes, while the real component represents staying in place (or purely reversing). Furthermore, we know that the real component cannot be on an axis or else the algebra collapses. So now we have three algebraic variables, taking up all three dimensions. Where has the real component gone? Can we just forget it entirely? How do we interpret what these rotations do e.g. to ? We know that:

But is no longer in our picture!

Consider that turning all the way around on an axis is, at least positionally, equivalent to staying in place. Algebraically we can say . But we also know that . This means must cycle with in exactly the same 4-step procedure as in the 2D case.

The Eye of the Storm

It's a Real Twister

The algebra doesn't collapse, but things are getting a bit carried away! We have an algebra that can rotate around all three axes, but it does something else. Part of the component parallel to the axis of rotation, the part that is twisting in place, is getting cycled toward . We were only considering the real component to be part of the action, meaning roughly stay-in-place, but now its part of the resulting position! Meanwhile, the component along the axis is liable to collapse to or to end up going the opposite way entirely. We only know where its "supposed" to go because of the context of the action that generated it.

Let's look at what the algebra is telling us. Its saying that the stay-in-place and rotate-in-place behaviors are two aspects of the same overarching behavior, that of not moving. They both have the same effect on the final position, but how they get there is different. Therefore the "position" that multiplication gives back to us has its axis split in two, the part that stayed and the part that twisted.

After doing a multiplication, one option is to step out of the algebra and use the pythagorean theorem to sum up the twisted component and the axis, but this completely defeats the purpose of having an algebra! We need to be able to undo the twist without undoing the rotation. Another two-step process is in order.

Controlled Opposition

How to Pull the Strings

Is there anything fundamentally different between the two cycles that will allow them to be separated? Recall that the order in which axes multiply matters because it keeps track of which axis is rotating the other. We need to contrast this antisymmetric behavior in the plane of rotation, where order matters, with the symmetric behavior of twisting, where the order is irrelevant.

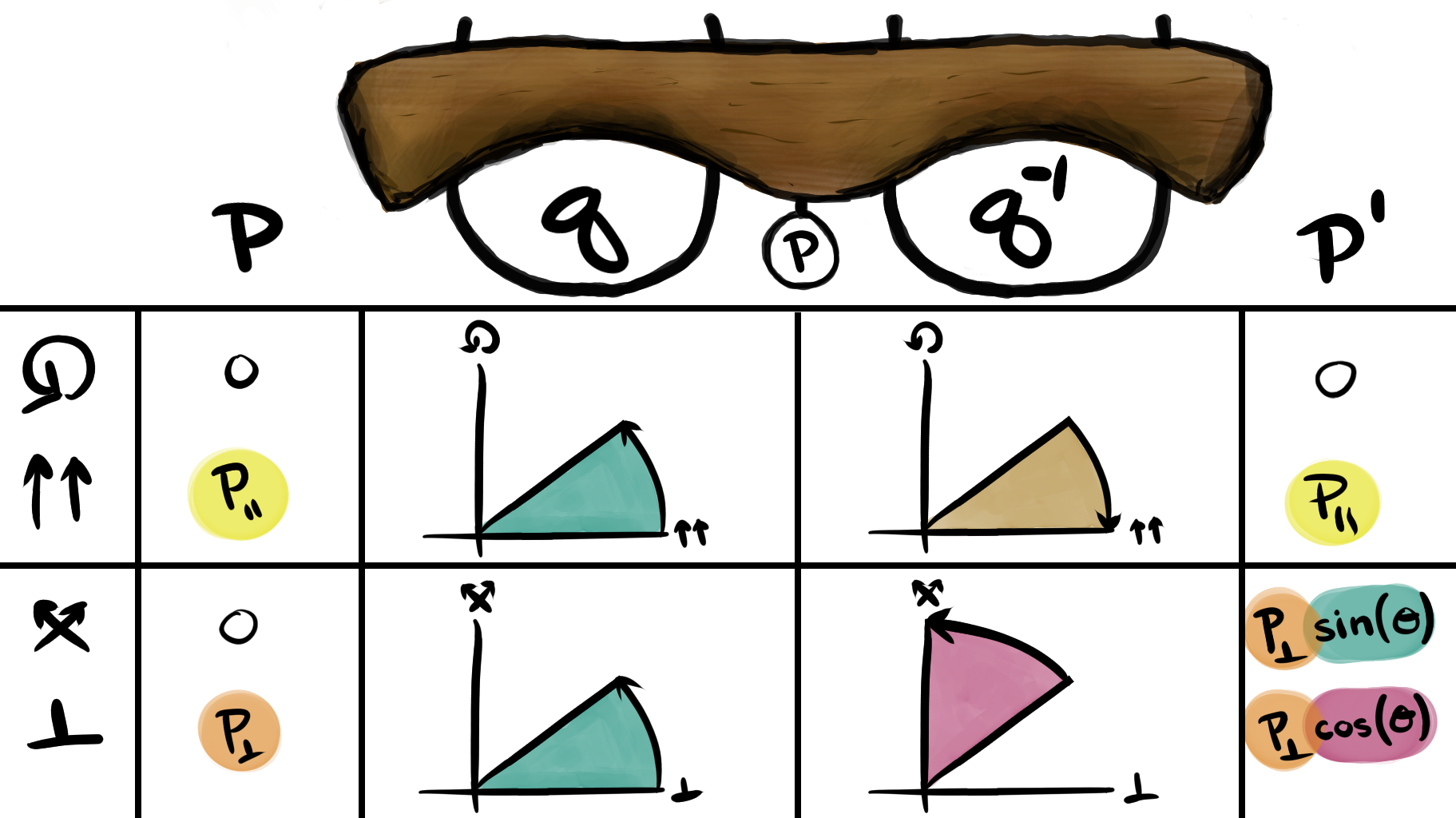

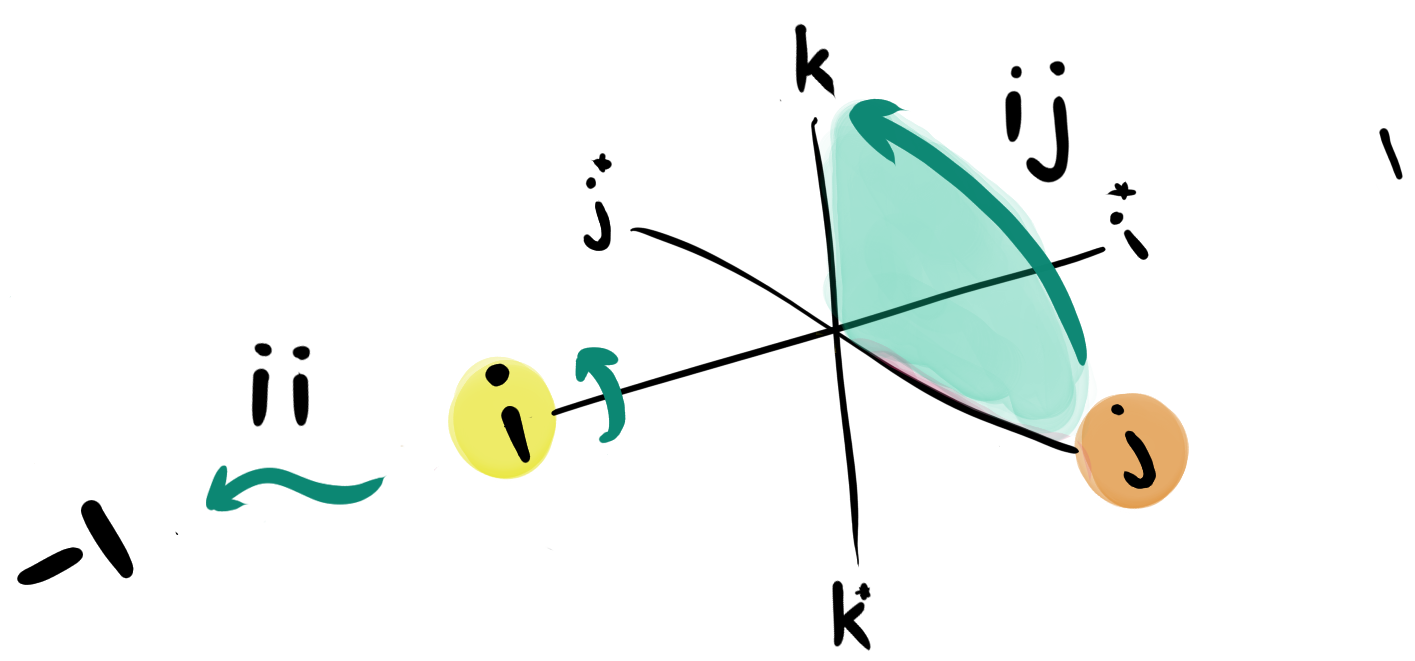

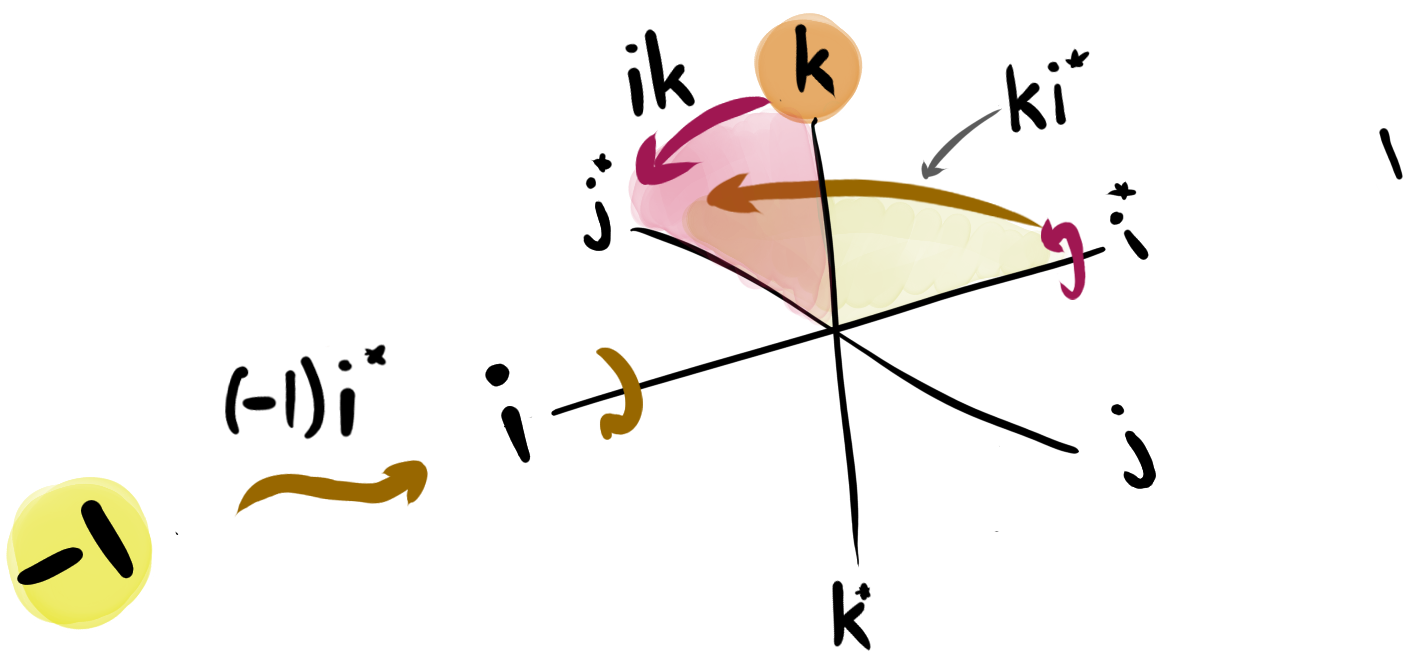

Let's first consider multiplying the point on the left by , represented by the green arrow. The component, represented by the yellow dot, is along the axis of rotation while the component, represented by the orange dot, is in the plane of rotation:

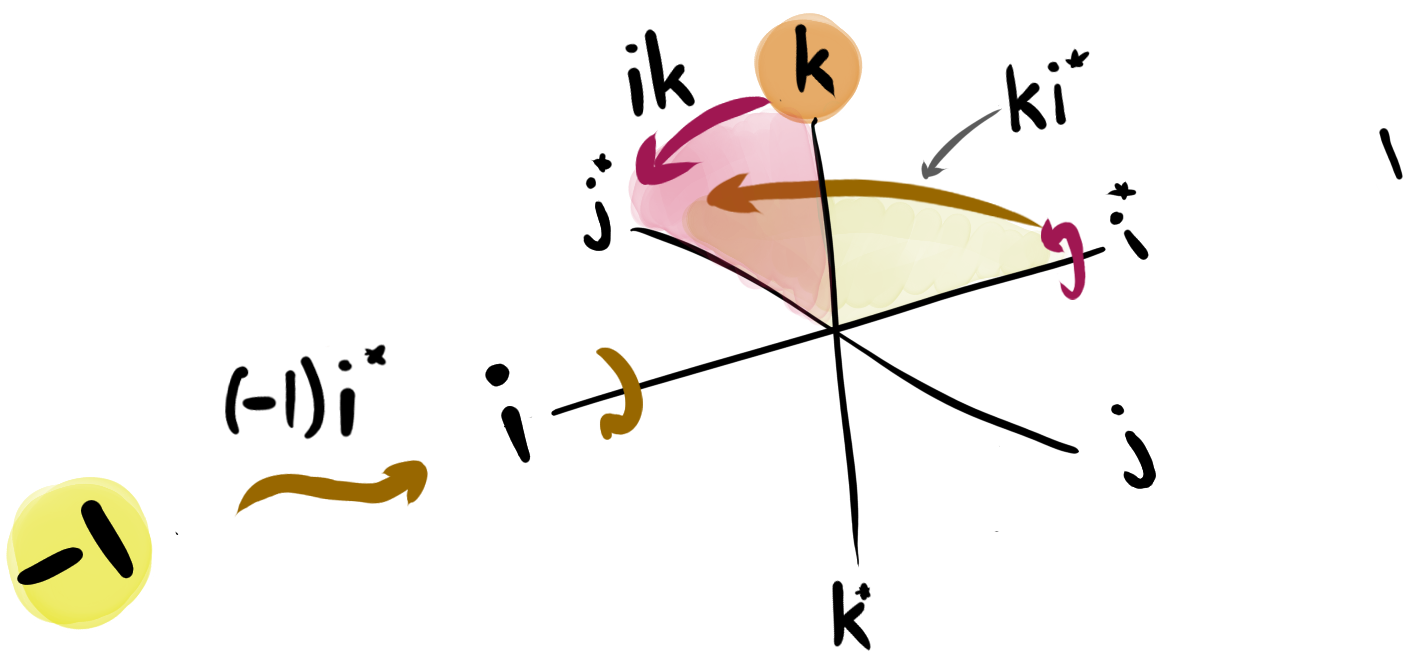

This takes and . We can consider the term as signifying that the parallel component, , has done a counter-clockwise twist, while has undergone a quarter rotation. Now we'll undo the twist by multiplying by the conjugate, , but this time we'll multiply on the right, as represented by the gold arrow:

First note that the twisted, parallel component at has been untwisted back to , as expected from multiplying by the conjugate. But what happened within the plane of rotation? What does it mean to multiply on the right by ? The algebra tells us that this is the same as if was multiplying on the left, i.e. as if was the axis of rotation, represented by the gold arrow . But what does this mean as an operation on ? One that takes to ? Notice that, within the plane of rotation, this results in the same action as the first rotation, the one that resulted from multiplying by on the left.

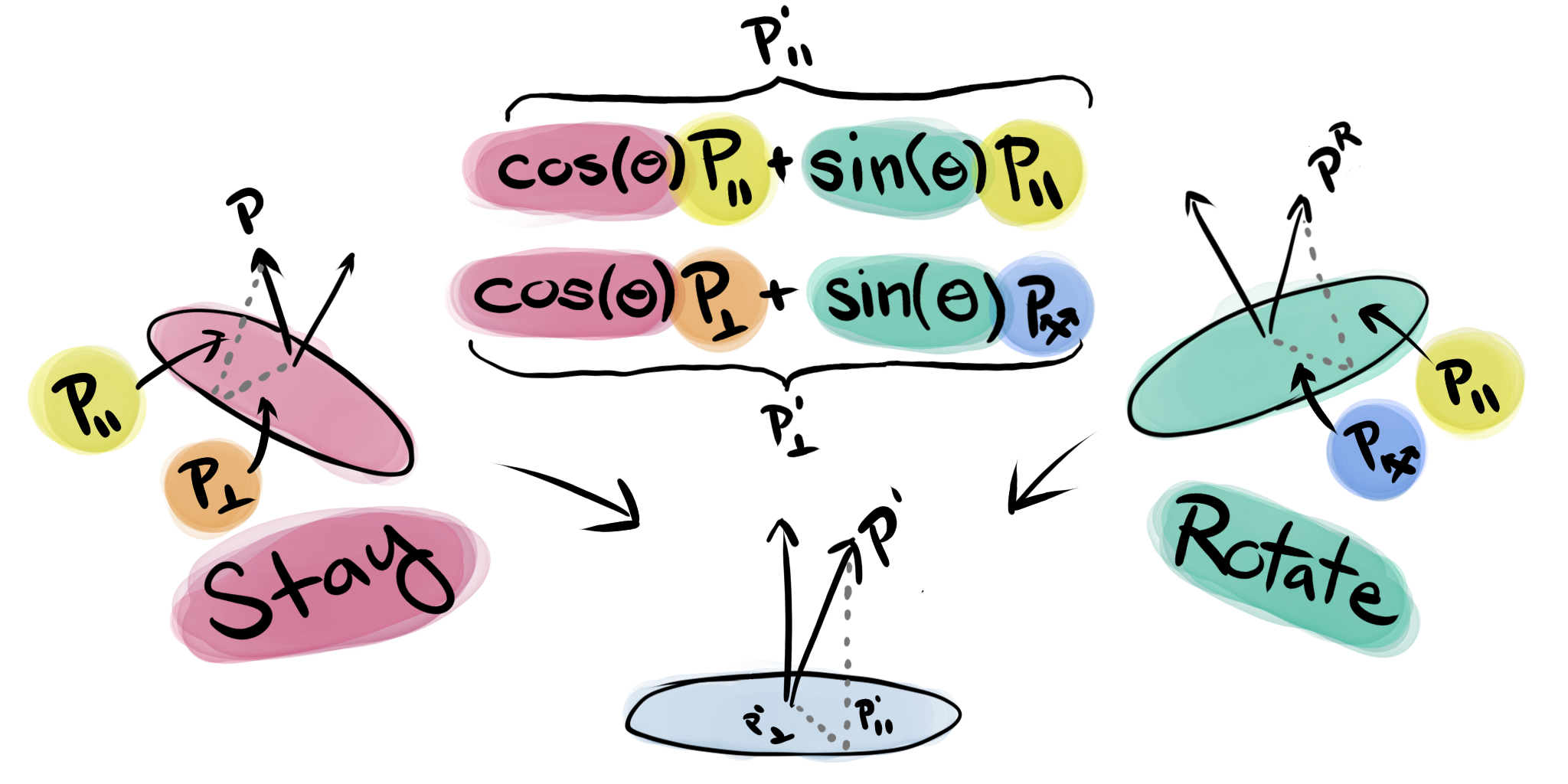

By both taking the conjugate and multiplying on the right we are both rotating in the opposite direction and from the opposite side, such that the two reverses cancel each other out. Meanwhile, the axis of rotation only cares about which direction the rotation goes, i.e. whether or not we are using the conjugate. By leveraging this difference, the rotation doubles up and the twist cancels out, leaving movement only in the plane of rotation!

By multiplying on the left by and the right by , we have performed a counter-clockwise rotation around . This time we have gone a full half turn, as opposed to a single quarter turn in 2d, by performing 2 quarter turns in order to do and undo the twist along the axis of rotation. You can get a feeling for this interaction between left and right multiplication here:

The fact that we have to do and undo the twist means that the amount of rotation done in each step gets doubled up on the whole. This double action is the reason why quaternions use half the angle of the rotation they are meant to represent. Therefore, in order to perform a rotation of angle around axis , we can use a quaternion that looks strikingly similar to a complex number representing a rotation, but the angle is divided in 2:

So we've rotated a vector around for an angle . But, seeing as we've defined everything symmetrically, could have been any unit vector involving around which to rotate! Any quaternion with a norm of , called a versor (meaning "turner"), could be substituted in for in order to rotate around its axis.

Notice what we've achieved in terms of two other common ways of representing 3d rotations, Euler angles and angle-axis. Euler angles represent rotations purely around one of the three axes, which we used as a base case to help us derive the quaternion algebra. Defining this algebra in a general way has then left us with a type of angle-axis representation, but one that encodes half the angle rather than the full angle so as to be able to do and undo the twisting action!

Getting Yoked

Its a Push and Pull

This process of placing a versor and its conjugate on either side is called conjugation. The word conjugate shares a root with the word yoke, as in a beam that binds working oxen. We can say that we have conjugated by in order to rotate it, so and are related through by conjugation. I suppose that versors are like oxen, working hard to rotate around the axis via the yoke of conjugation!

Tracing through the operation, we can see how the real component, the twist, gets cancelled out, while the rotation doubles up: