Dimension 1

... Measure!

BANG! Suppose now there is a dimension, a way to measure apart, and a ray of light shines forth from the origin. At some arbitrary distance we can declare that the ray has traveled unit. This basis unit enables us to measure distances to other points by comparison.

Moving a point from the origin is called a translation, meaning "to carry across". If we carry a point and put it down, we say we have changed its "position", meaning "the spot where it has been put". Translation can be represented by addition:

What have we lost by adding this dimension? The simplicity of the singularity. It is no longer the case that there is only one point and all actions take this point to itself. Equations are easier to deal with when is the only element, but we've exchanged that singular structure for points on a line. These can at least be ordered with respect to their directions and distances from the origin, with each having its own place in the line.

Snakes and Ladders

A Hop, Skip, and a Jump

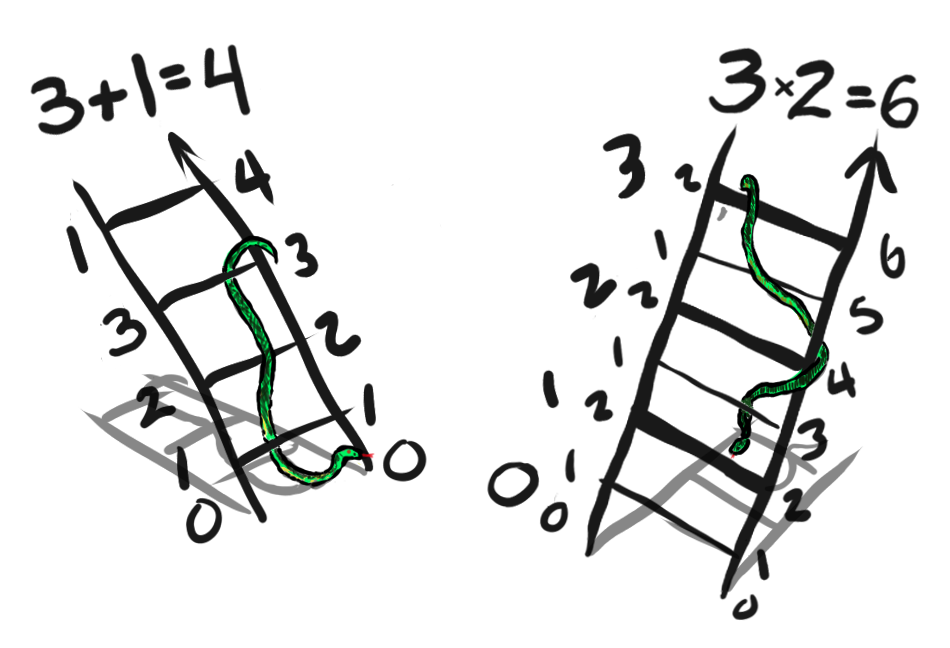

Imagine scaling a ladder with rungs that are one unit apart. The number of rungs on the ladder is proportional to its length. Accordingly, lengths along dimensions are called "scalars", since they tell us how many "rungs" it would take to scale to a given position. We can add and multiply scalars to produce different translations. When we multiply two scalars together, it is as if we are using one whole ladder as the rungs of the other.

When multiplying by , we stay on the same scale and at the same point . In this sense , considered as a command, says, "just be yourself". Accordingly, it is called the multiplicative identity. Contrast this with multiplying by , which says, "Wherever you thought you were going, you're here now!" One could call multiplying by "termination", since once there is no distance between the rungs of a ladder, scaling them doesn't get us anywhere. is the end of the line, the terminus.

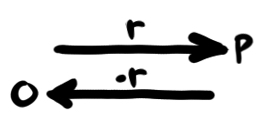

Okay, but what if we slide down a snake? What action takes us back toward the origin? This is the "inverse" translation, meaning "turned inward". But where do we get if we keep going? The respective positions reached by going forward vs backward are "opposites", meaning "placed across". They are called additive inverses, since adding them together yields .

The movement of going from a position to its opposite, or vice versa, is called a "reflection" meaning something that is "bent back". In order to "bend back", we can either do two inverse translations or scale by .

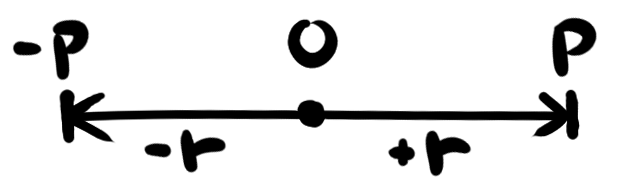

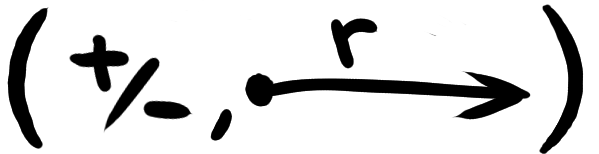

Notice that we've gotten two directions, forward and backward, out of a single dimension. In this way, even though we can represent both a point and the action of getting to that point with the same number, we can think about the action as specifying two distinct aspects of behavior, namely "which direction?" and "how far?". We can put these two separate pieces of information next to each other as component coordinates, where the phrase "component coordinates" means roughly "parts placed together in order".

There and Back Again

It's All About the Journey

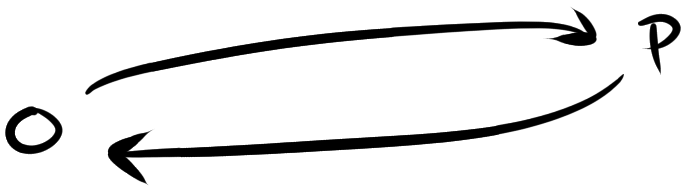

Suppose we go on a walk and return to where we started. From the perspective of our final position its as if we never left! If we want a record of our journey, we have to consider the distances travelled in each step separately. Then we could add up all the "how fars" while ignoring the differences in direction.

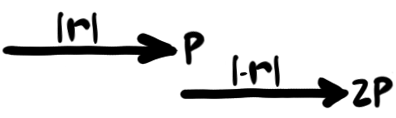

Taking just the distance without regard to direction is called the "modulus", meaning "little measure". Here in one dimension we can just take the absolute value. Consider what happens when we sum the positions reached by each half of our walk vs how far we've travelled:

Notice that if we want to take a walk of distance and get back to where we started, we'd have to go a distance of there and back again. The modulus doesn't care what direction we go and sums up the same either way. This behavior is called being "even". Meanwhile, going in the opposite direction changes the sign of the resulting position. This is called being "odd". The difference is that the position is taking the orientation into account while the distance travelled is not.

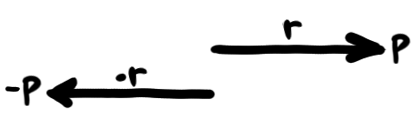

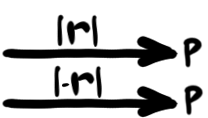

Now suppose that, instead of a walk, we're in a pistol duel with a mortal enemy. We've agreed to stand back-to-back and both take paces before turning to shoot. By taking the difference between our two journeys, we can see the total distance between us, as well as the fact that we're walking the same distance:

Here we have isolated the even and odd behaviors by either summing up or taking the difference between two translations, and given an example of why we might want to consider one or the other.